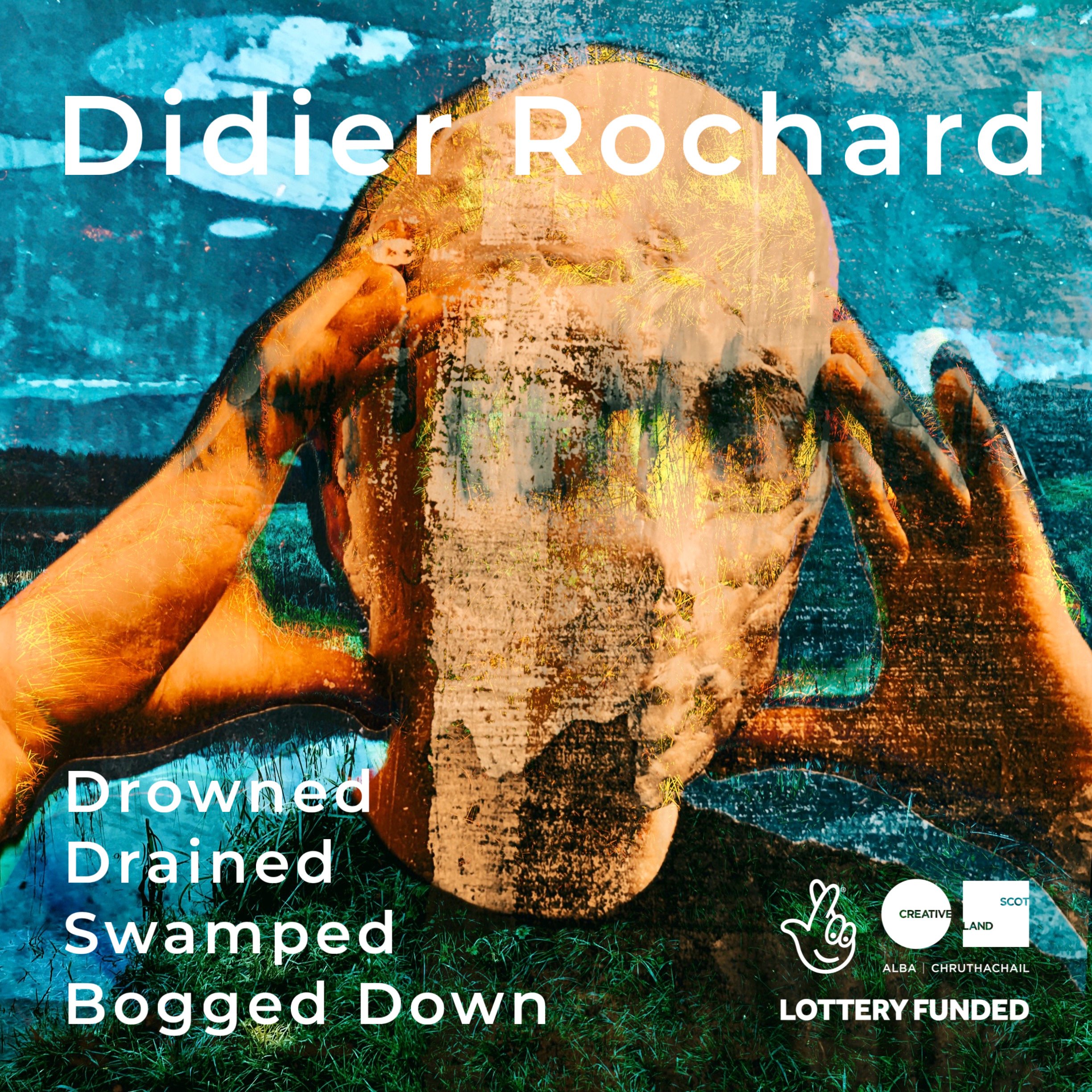

Drowned, Drained, Swamped & Bogged Down:

Initiating A Creative Exploration Of Mythterious Scottish Marshes & Wetlands

Landscape 3: rannoch moor

Rannoch Moor is an expanse of around 50 square miles (130 km) of boggy moorland to the west of Loch Rannoch in Scotland, where it extends from and into westerly Perth and Kinross, northerly Lochaber (in Highland), and the area of Highland Scotland toward its south-west, northern Argyll and Bute.

Habitats identified: Peat bog, wet heath, quaking bog.

Read about my landscape visit below and view my creative responses here.

To fully appreciate Rannoch Moor, one must have an appreciation of blanket bog or blanket mire, also known as featherbed bog - an area of upland peatland, forming where there is a climate of high rainfall and a low level of evapotranspiration. This allows peat to develop not only in wet hollows but over large expanses of undulating ground. The blanketing of the ground with a variable depth of peat gives the habitat type its name.

A large proportion of blanket bogs are already degraded as a result of draining, burning (managed burning and wildfire), over grazing and atmospheric pollution. Many blanket bogs are now relatively dry and may already have lost the peat forming species such as Sphagnum mosses, which may have been replaced by other species such as heather or moor grass.

It was mid-May. I travelled for 2.5 hours by train from Glasgow Queen Street to Bridge of Orchy - a village named after the crossing of the river Orchy, constructed by British Army during the pacification of the Highland Clans following the Battle of Culloden in 1746. I had considered wild camping but given the weather forecast I opted for a simple glamping pod beneath a very tall Scots Pine, overlooking an area of moor grass and mixed forest. The screech of young owlets calls kept me awake at night but I didn’t mind - this was excellent habitat for them. Nearby, abandoned houses in the forest hinted that this was a less-than-ideal habitat for some humans. It was mid-May but a gloom clung to the landscape’s haunting beauty.

With rainclouds gathering, I had abandoned my more ambitious plan to walk right across Rannoch Moor from one of the UK’s most remote train stations at Rannoch and along Loch Laidon to Kinghouse. The hike would be very exposed with nowhere to shelter and the path was unmarked in places. I was here for the areas blanket bog and quaking bogs and I didn’t fancy getting stuck in one in the rain. Instead I took a bus up the A82 close to the Glencoe Ski Centre and cross part of the moor and Black Mount, walking along part of the West Highland Way back to Bridge of Orchy. Even in the worst weather this meant I would encounter other walkers tackling this more popular route.

As the bus weaved its way uphill to the start of my route, I was struck by the vast openness of the landscape. And its wetness - the landscape surface dotted with lochs, lochans, peat bogs and streams. The entrance to Glencoe rose from the plateau like the gateway to a mythical realm. It really was an otherworldly landscape. Rannoch Moor is one of the last remaining wildernesses in Europe. The inverted triangle of the moor is a roughly level plateau that sits at an altitude of around 1,000 ft. The moor is surrounded by mountains that rise to over 3,000 ft in places. I had read that the entire landscape was often shrouded in thick grey mist. Luckily for me, the view today was clear - and the views were spectacular. I felt like an ant compared to the scale around me. Interesting then that the moor is one of the few remaining habitats for the narrow-headed ant. I set off walking thinking I should be careful not to step on any.

Rannoch Moor is one of the last really wild places in Scotland. And it appeared empty. Silent nothingness. Even the air was still. But I knew that actually the entire landscape was alive - the entire view carpeted with blanket bog, moor grasses and heather. Under that blanket, many many things were alive - hidden from view. The peaty ground was spongey beneath my feet and very pleasant to walk on before I joined the gravelly drover’s road across the moor.

The ghostly sound of a curlew drifted on the wind. Curlews, known as “whaup” in Scots, due to the nature of their call - related to Old English “huilpe”, imitative of the bird's cry. Whaup is also the name of a little goblinesque dawrf creature in legend with a logn neb or bill, shaped like a pair of tongues that it used to carry away ill-doers. It appears in Walter Scott’s Black Dwarf as one of the “lang-nebbit things”. Another legend associates the sound with the calling of Gabriel’s Hounds, the Angel of Death with his hunt for the souls of the dead and dying.

I should also look out for an array of iconic Scottish species - red deer, golden eagles and black grouse, as well as delicate plants like sundews and bladderworts. Ancient standing stones, burial cairns, remnants of shepherd’s huts and old drover routes also hinted at the human memory etched into this landscape.

The day had turned out to be hot and there was nowhere to shelter. I stopped to rest by a stream and removed my hiking jacket. Exposed bog wood lay like bones above dark peat. The humanoid shapes of the grassy tussocks and rocks conjured images of people here - burials perhaps.

I also thought of the lonely figure of the bean-nighe by the stream, next to the drover’s road. One of my favourite folk tales, the bean-nighe is from Scottish Gaelic for “washerwoman”. A female spirit she is regarded as an omen of death and a messenger from the otherworld. She is a type of ban-sith (anlicised as banshee), that haunts desolate streams and washes the clothing of those who are about to die. She is also called the nigheag na h-ath or “little washer of the ford”, or bheag a bhroin, “little washer of the sorrow”.

She can be seen in lonely places (like this!) washing the blood from the linen and grave clothes of those who are about to die. Differing traditions ascribe her powers of imparting knowledge or the granting of wishes if she is approached with caution. It is said that mnathan-nighe (the plural of bean-nighe) are the spirits of women who died giving birth and are doomed to perform their tasks until the day their lives would have normally ended. It was believed this fate could be avoided if all the clothing left by the deceased woman had been washed - otherwise she would have to finish this task until death.

On the isles of Mull and Tiree she was said to have unusually long breasts that interfere with her washing, so she throws them over her shoulders and lets them hang down her back! Those who see her must not turn away but quietly approach from behind so that she is not aware. He should then take hold one of her breasts, put it in his mouth, and claim to be her foster-child. She will then impart to him whatever knowledge he desires. If the washing belongs to himself or any of his friends, then he can stop her from completing her task and avoid his fate.

The bean-nighe is said to sing a mournful song as she washes the clothing of someone who is about to meet a sudden death by violence. She is often so absorbed in her washing and singing that she can sometimes by captured, following which she will reveal who is about to die and also grant three wishes.

She is sometimes described as having various physical attributes including only one nostril, a large protruding front tooth or red webbed feet.

I think she’d fit right in here in this lonely landscape next to the drover’s road.

As I descend from the moor, a new feature appears - trees. And with them there is suddenly life. Bird song and movement up in the branches. Mosses and lichens carpet trucks and branches - I’m not sure whether the trees are rising from the earth or being pulled down into it. Sprawling spidery roots tease their way along the surface of the peat, trying to find gaps in the rock beneath. I watched a small herd of red deer run across the path in the distance.

As heather turns to grass, the hills begin to roll gentley and the landscape feels altogether more welcoming. I reach an abandoned building with a beautiful tree growing from within - its full leaves alive with birdsong in the afternoon sunshine.

Still, there is a fascinating sadness in abandoned buildings. Lives lost. Plans changed. Dreams faded.

I think of the tragedy of the Highland Clearances. Of people forced to leave this stunning landscape. The empty beauty of this part of Scotland actually associated with so much cruelty, injustice and violence. Ordinary lives destroyed so that the wealthy could enclose sheep and have grouse to shoot. I know I would encounter more about crofting on my next landscape visit. What a place to leave behind.

Completing my descent off the moor, I was struck by a dramatic contrast. The rows of industrial forest vs the remnants of gnarled ancient pines, their tall trunks twisted and characterful. High up in their branches, flashes of incredible bright red. Not burnt ginger like a squirrel, but bright punchy red - vibrant against the rusty landscape. Crossbills!

I had never seen a crossbill. They were in the back pages of my bird guide as a child, along with spoonbills and golden orioles - birds that simply felt unobtainable for a child living in the Peak District. I hadn’t really considered them real birds But here they were - lots of them! Small pine cones were falling like rain on the path as the busy birds raided the branches. Crossbills are specialist feeders on conifer cones, and the unusual bill shape is an adaptation which enables them to extract seeds from cones.

There is a story that when Christ was crucified all the birds and animals grieved, but only one, a plain little brown bird, tried to help him. This little bird stayed near the Cross, and when the nails were driven through hands, the bird fluttered down and tugged on them to draw them out. The bird struggled until his little bill was bent out of shape and his feathers dyed with Christ’s blood. Although the bird ultimately failed, Christ saw his efforts and smiled and thanked him. And ever since, says the legend, the bird's feathers have been red and its bill crossed.

Another explanation is that the scissor-like bills are useful for chipping the scales off the cones, in order to reach the seeds beneath. The conifer detritus landing on the path (and on me) would suggest this was a more likely explanation.

Reaching the river that would guide me back to my glamping pod, an area of reedbed hinted at the water flowing out of sight right across this landscape.

A true wetland, on an enormous scale.