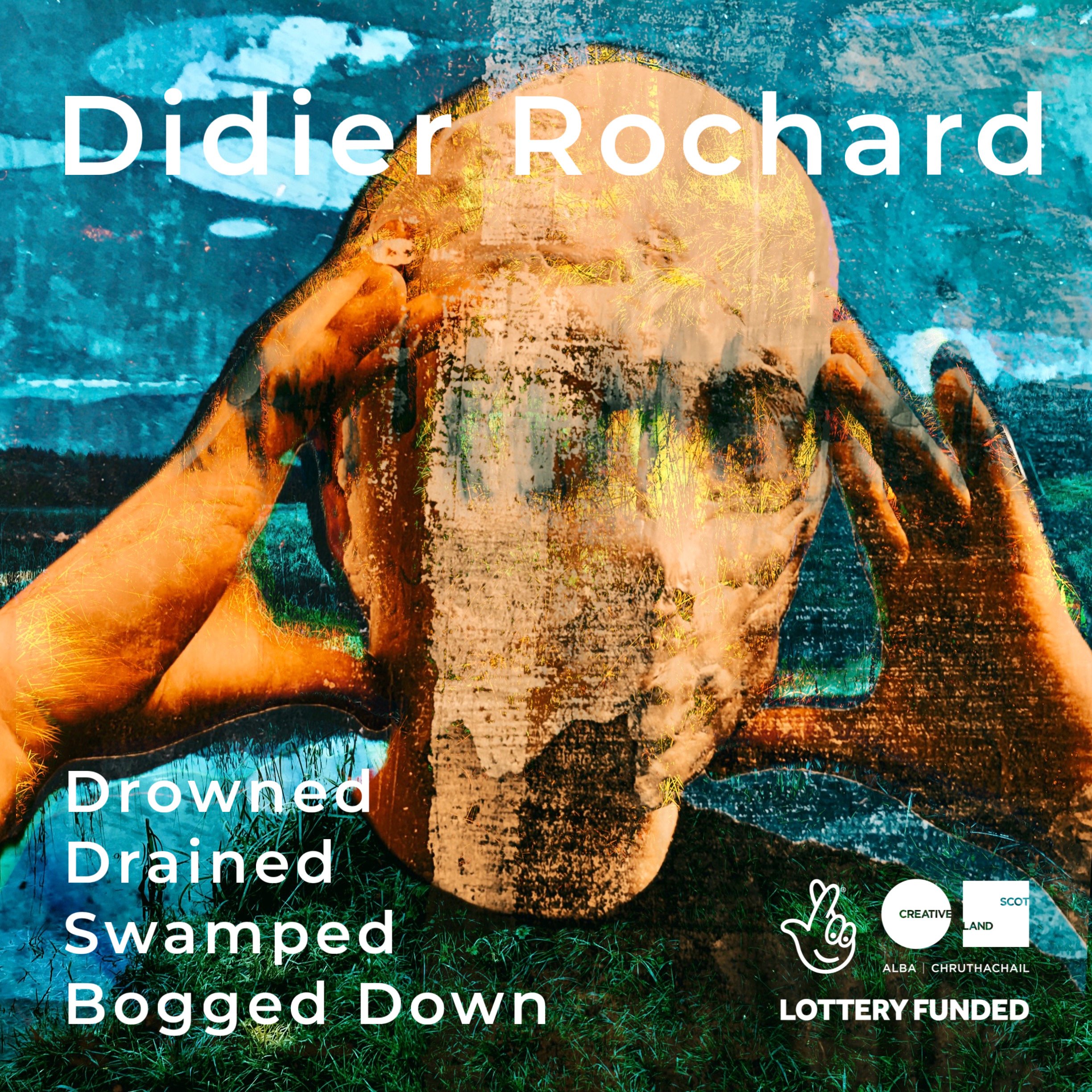

Drowned, Drained, Swamped & Bogged Down:

Initiating A Creative Exploration Of Mythterious Scottish Marshes & Wetlands

Landscape 5: AbernEthy FOREST

Abernethy Forest is a remnant of the Caledonian Forest in Strathspey, Highland, within the Cairngorms National Park. It is the largest area of natural pine forest in the UK.

Habitats identified: Wet woodland, springs, flushes and seepages, peat bog.

Read about my landscape visit below and view my creative responses here.

Abernethy National Nature Reserve (NNR) is one of the largest and most inspiring reserves. It stretches from the River Nethy to the top of Ben Macdui, high on the Cairngorm plateau. Abernethy NNR encompasses one of the largest remnants of Caledonian pinewood, as well as moorland, wetlands and mountains. The reserve is home to a host of specialist pinewood and upland plants and animals.

Taking the train from Glasgow, I stayed in the Highland town of Kingussie - my room affording a glorious view of the first in the distance - ahead of a full day of walking from touristy Aviemore the next day. I had planned to walk through the forest to Loch Garten, a place I’d wanted to visit since childhood, due to the osprey population here. The osprey was extinct as a breeding bird in Britain, largely due to egg and skin collectors during the 19th and early 20th centuries. They successfully recolonised close to Loch Garten in 1954 and are now the most famous summer visitors to the area.

Setting out from Aviemore, I was immediately struck by the wetness that clings to this landscape - evidenced by the moss and lichens clinging to every tree and fencepost, bringing an ancient and otherworldly feel. Approaching the first stretch of forest, I was struck by the intense smell of pine.

As well as ospreys, the RSPB’s Abernathy National Nature Reserve is the best place to see bog woodland in the Cairngorms. Bog woodland has a primeval feel of sparse stunted Scots pine and birch co-existing alongside the bogs and mires of the forests. These woodlands highlight the way in which nature often blends the boundaries between one habitat and another. Parts of the forest have previously been drained but projects are restoring drained areas of peaty soils back to near natural bog. This is achieved by blocking artificial drains within the forest either by machine or hand.

Other restoration projects included winching over trees to mimic wind-fall, creating open areas within forest that had previously been densely planted for commercial purposes. The exposed root plates create micro-habitats for fungi and invertebrates, contributing to greater biodiversity.

In addition to the tall (and stunted) Scots pines, the other most striking thing about the forest is the understory of plants which carpet the forest floor. The density and richness of different plants was quite extraordinary. The shrub layer considered of juniper (an indicator of ancient forest), aspen, birch, rowan, bird cherry and alder. The ground layer a tapestry of heather, blaeberry and cowberry. Broad-leaved trees are far rarer here. In the past, broad-leaved trees were selectively cut for firewood and charcoal, or removed as “weeds” from the commercially managed pinewoods.

Grazing deer have also had an impact on the ability of broad-leaved trees to re-populate the forest. The winching-over, seen earlier, was enabling broad-leaf trees to establish on the tops of the roots plates out of reach of browsing deer.

Most-clad walls and ruins spoke to past human inhabitants of the forest, long gone - the stones returned to nature. There was a sense that the forest would reclaim anything that stood still for too long.

Small pools and streams punctuated the forest. A larger waterway opened up on the right hand side of the path, bleached tree skeletons rising from the surface. These water bodies provided perfect habitat for the 12 species of dragonfly and damselfly which can be found within the reserve, feeding on the clouds of midges over these pools. A board showed species to look out for in this special place, part of the last remaining 1% of the ancient Caledonian pine forest.

The trees in the bog woodland are stunted, but many are as old as the tallest trees nearby. The biggest in the forest are nearly 300 years old and escaped being cut for use in the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). The area was replanted in 1860 - different generations of trees contributing to this true mosaic habitat, dense with life.

A sign indicates that every hummock on the forest floor was once a tree stump or boulder, now covered in moss, plants and even small trees. Lichens - tiny, flat, leaf-like growths - kick-start this process by breaking down the surface of rocks and tree stumps, forming soil. Pine needles and organic matter blow in and settle on them, providing nutrients for mosses and eventually other plants. Hummocks are a tell-tale sign of ancient forest.

Holes in dead wood provide nesting places for birds and bats, while rotting trunks are colonised by the insects on which they feed. Nothing goes to waste in the forest.

Reaching the loch, I am greeted by the chatterings of siskins. No sign of ospreys or red squirrels though, let alone the other iconic species that call the vast reserve home - even golden eagles, wild cats and capercaillie. I could cover only a small stretch of ground in one day but could easily spend weeks exploring this enormous reserve and its inhabitants.

The Visitor Centre was busy with people looking to catch a glimpse of ospreys, though today none were at the nest. I stopped for lunch and spoke to a very knowledgeable guide about the exciting conservation work being done here.

Around the pools I spotted sundews - a predatory plant that has evolved to catch insects on sticky hairs. I watched a fly fighting for its life - it wouldn’t win. I also learned that Diving Beetles can be found in the pools of water that form from the upturned roots of windblown trees. It seemed the dead trees here were as important as living ones - part of that great cycle of life.

Biodiverse habitats like this contain a great many niches where different species can thrive. I was impressed with some of the activities and signs to engage children at this future-facing visitor centre.

Continuing the walk, the weather turned. Rain. Lots and lots and lots of rain.

Despite getting completely soaked through to the skin, even beneath the dense canopy of the forest, I still managed to capture some beautiful moody shots of interesting tree forms.

While I felt cold and wet, the forest seemed to glisten and sing - water and wetness - responsible for the magic of this place.

The next day, having dried off from my soaking the day before, I set off for a short walk in Aviemore - to the Craigellachie National Nature Reserve, close to the Youth Hostel.

Rather than pine, this time the landscape was mainly birch woodland, open glades and tree-fringed lochs, rising to a craggy summit. If I squinted the landscape almost looked like Australia - eucalyptus around billabongs.

I headed uphill, to climb the crags around Aviemore - the top viewpoint would grant fantastic panoramic vistas of Aviemore and the Cairngorms, and signs told me to look out for peregrines.

The air was thick with wet heat and the smell of thyme. Over 350 different species of plants have been recorded at Craigellachie, including shade lovers like the delicate dog violet and the white, spring flowering wood anemone.

Craigellachie’s trees were thriving on poor, well-drained soil. Individual birch trees that had grown out to their full form had an elegant look, with their delicate branches and cascading tresses of light green leaves - the trees are often given the name ‘Lady of the Woods’.

Other trees included aspen, rowan, hazel, bird cherry, willow and Scots pine, as well as juniper, complete with glossy berries, and bog myrtle.

I was defeated by the heat and humidity before I reached the top of the cliff, but nonetheless I was rewarded with some wonderful views back over the forest.

I had come to Abernathy expecting iconic animals and birds. But as I returned to the train, I was realised that it was the plant life that made this trip - the forest itself.

Feeling slightly deflated, a darting movement in the treetops caught my eye - a red squirrel?!

I scanned the treetops. No, just a robin.

But then, my eyes shifted focus to the open sky behind the tree - and there, in full view, sailing right over the top of me - the unmistakeable silhouette of an osprey.

Huge, magnificent and magical.

A final gift from the spirits of this wonderful place.