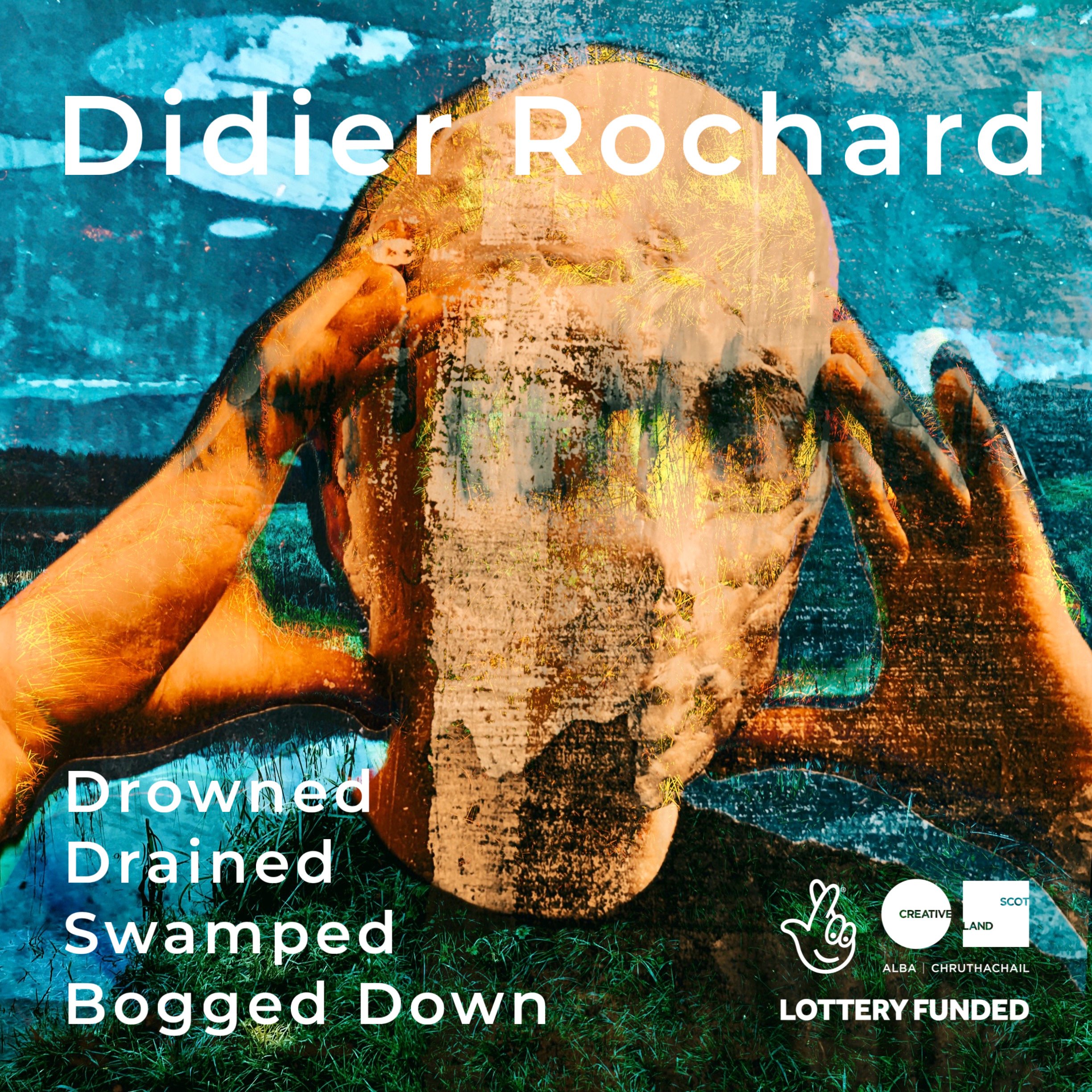

Drowned, Drained, Swamped & Bogged Down:

Initiating A Creative Exploration Of Mythterious Scottish Marshes & Wetlands

Landscape 6: Forvie Sands

The Forvie National Nature Reserve is located north of Newburgh in Aderdeenshire. The reserve includes the Sands of Forvie, which are the fifth largest sand dune system in Britain, and the least disturbed by human activity.

Habitats identified: Dune slacks, wet grassland.

Read about my landscape visit and view my creative responses here.

Setting out by bus from the silver city of Aberdeen where I was staying, the landscape quickly turned to gentle rolling farmland, lush and green - quite different to any of my other visits so far. The granite city of Aberdeen had been deeply grey, against grey sky, as if colour had been desaturated from the streets. The same grey sky met me at the top of the country lane down to the reserve. The cows didn’t seem to mind. A boat in a field and the cry of seagulls told me the sea was nearby over the horizon. Otherwise the place had that still silence that seems to come with tidal estuaries.

At the gateway to the reserve I stopped to take a quick look inside the small visitor centre. I was hear to see the dunes and another unusual wetland habitat - dune slacks.

Dune slacks are depressions in the dune system that have formed because of wind erosion down to the water table. Often they are seasonally flooded and low in nutrients.

It’s easy to look at a sand dune and just see a pile of sand, but lots of different factors and processes are involved in making a coastal sand dune system. In fact, sand dunes have a lifecycle, with young dunes forming at the beach and old dunes pushed further inland.

Sand dunes are separated by dips, which are known as dune slacks. If these slacks erode far enough to reach the water table, freshwater pools can form, which form fantastic habitats for wildlife such as amphibians.

As I reached the dunes, the whole area was shrouded in sea fog. I had never seen a landscape like it.

The walk through the dunes was a silent one. The dunes seemed to cushion from all sound, including sea, wind and bird calls. At ground level, the ground was a tapestry of low-growing wildflowers, mosses, lichens and small woody shrubs between the pools - a mosaic habitat for sure.

The area is designated as a both a Special Protection Area and a Special Area of Conservation, as well as being a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It is a Category II protected area by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. It was easy to see why - it is truly a national treasure.

The Sands of Forvie are one of the largest areas of blown sand in Scotland. The sand is formed from the remains of sediment that was transported by rivers to the coast at the end of the last ice age. The sediment settled in the sea, but was gradually washed onshore by the action of waves and wind. The dunes are highly mobile, and can reach a huge 20 metres (66ft) in height. A place of stark beauty, especially in a thick sea fog.

The dunes seemed to go on and on in their undulating glory. I imagined being lost in this place in the fog - a horror story or a beautiful escape from the rest of the world.

Eventually climbing to the top of a dune I was hit by the roar of the North Sea - its waves hidden in the fog. I’d come out of the dunes and up to a cliff, and I was now looking down onto a sandy cove. How was I so high up? This landscape felt disorientating. At points the fog would clear and I would be treated to flashes of blue sky, then the grey filter would descend again.

I stopped to sit and eat lunch on the edge of the cliff, where I was suddenly hit by the call (and smell) of a colony of seabirds. I watched them while I ate my sandwich - mainly razorbills and kittiwakes juggling political life on the rocky ledges. I watched a fluffy baby razorbill perfectly nestled on a flat outcrop high above crashing waves. Every bit of this place seemed alive.

I continued along the path and around a sandy bay. Soon I would head inland to find the ruins of a chapel.

The way to the chapel was marked, and I was glad as the remains were neatly tucked into the dunes. The flora growing on the old walls acted as camouflage from a distance. These were the remains of medieval Forvie Kirk. The remains were dug out of the sand by a local doctor at end of 19th century when the piscina was unearthed (a sort of stone basin, used to wash the vessels of the mass). The church, dedicated to St. Adamnan, is first mentioned in the 13th century records of the Chartulary of Arbroath and has early associations with a foundation of the Knights Templar. In the vicinity of the church, the foundations of square huts, built of roughly-shaped stones and red clay, apparently of medieval period, were uncovered. This may be the site of the medieval hamlet of Forvie. Burials suggest that it became ruinous in the 15th century.

According to local tradition, the village was lost in 1413 during a nine-day sandstorm. In support, meteorological records suggest that in Aberdeenshire, severe gales and extreme tides did coincide in the August of that year.

According to local folklore, after the death of the Laird of Forvie his lands were inherited by his three young daughters. But either deceived by a wicked uncle, or driven from their home by a mob of villagers, the women were cast adrift in a leaky boat. And from the sea, they lay a curse on Forvie. If the women were ever to reach dry land, nothing would be found in Forvie but thistle, grass and sand. Their curse raised the nine-day storm and to this day Forvie continues to suffer its fate. There are also stories about a hidden passageway from the altar to nearby sea caves.

There was an unease about this place - a place buried - yet inside the heavy lichen-covered walls of the church, all felt still and sheltered, as if this is how it was always meant to be.

Walking back towards the sea I met another ruin - Rockend salmon bothy. Its fireplace is still visible. Even in the early 1990s, long after sand had crept up its walls, it was still a working site, but with the decline in salmon came the demise of the fishing industry.

Turning towards the beach, a dog walker was shouting her dog to come to heel. The dog was having none of it and was busy delightfully rolling in something, but what?

Getting closer I was hit by the powerful stench of rotting flesh and could now see the dog walker’s horrified face - it was a whale carcass, well-rotten. I had never seen such a thing.

This only added to the strangeness of this deserted, silent place, buried in sand and shrouded by fog. After taking a few photos I couldn’t stand the smell any longer and walked on along the beach, only to be greeted by another carcass - this time a seal.

The seal-haul at Forvie is well known, though the carcass is the only seal I saw this day. A cordon and sign prevented further access up the beach, due to the breeding tern colony. Forvie has the largest breeding population of sandwich terns on Scotland’s east coast and they nest in their hundreds in the dunes. These elegant birds have an enchanting courtship ritual, with the male offering fish to the female.

I headed back inland. The large areas of bare sand and shifting dunes conjured the Sahara Desert. In some of the slacks lay vast quantities of small pebbles and shells - a sign that water had been here.

Stone Age and Bronze Age people lived and hunted here before the sands came. Among the dunes there are traces of their lives, like the mounds of shells or middens they left behind. A range of shell middens have been found here at Forvie, along both shores of the Ythan estuary. During excavations in 2010, it was found that the shell sequence at one of the middens extended down through some 2.9m of deposits and extended for over 35m in length. It is thought that some of the latest shell deposits date from as late as the medieval period and that some may even be Pictish - that most mysterious group of ancient people.

On leaving the dune system I was met by twisted windswept trees above meadows alive with wildflowers and bees busy on the tall necks of foxgloves.

I headed along the estuary and stopped to marvel at the vast array of coastal birds active in the shallow waters - herons, plovers, eiders, shellducks, all sorts of wading birds and, further out, the angelic terns diving into deeper water.

It was as if nature had banished humans from this place and it had been reclaimed by the rightful residents.

The sands had delivered the message loud and clear.

After breathing it all in for a final time, I realised my landscape visits had come to an end. Six remarkably different locations.

I felt privileged to experience them.

Now, back to the studio.