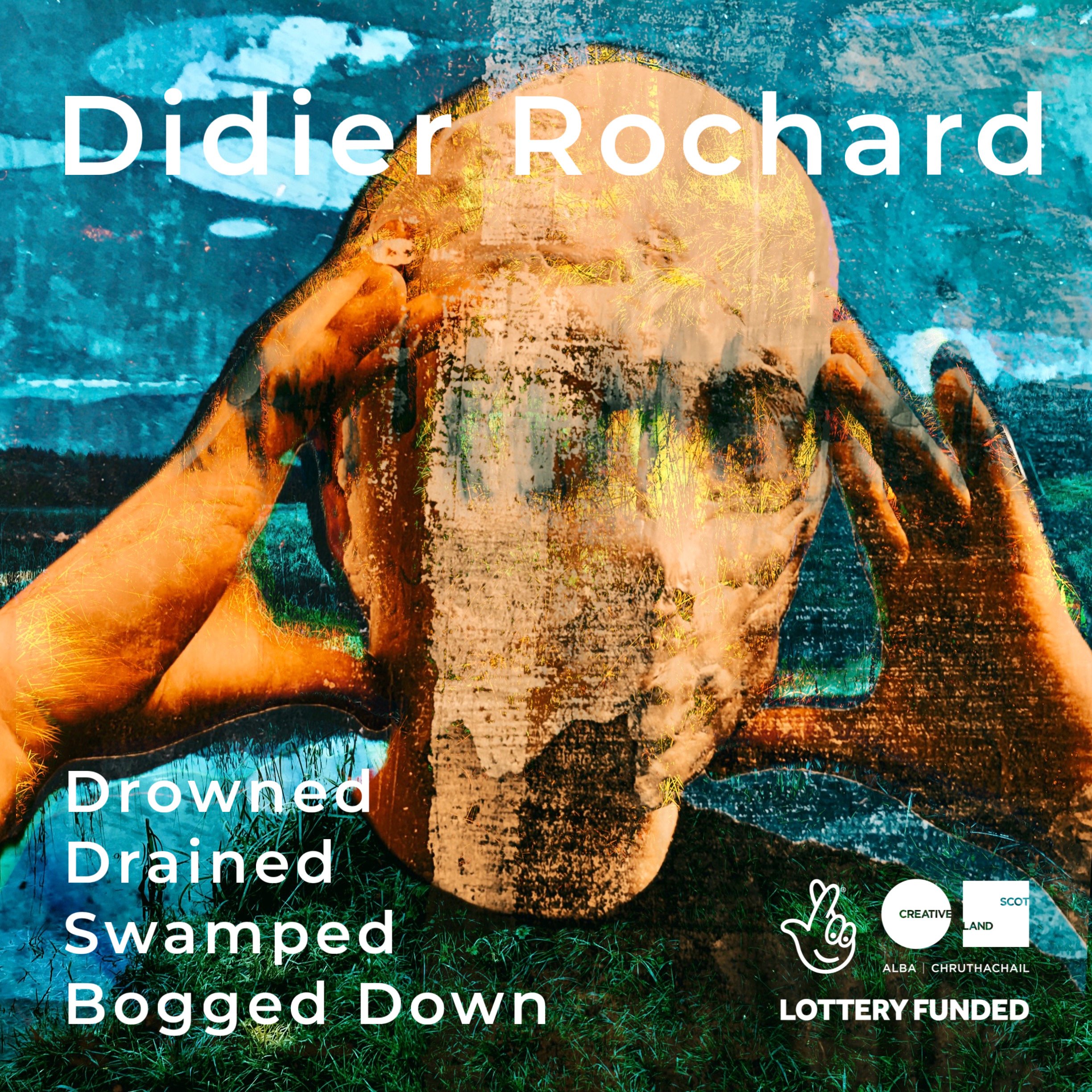

Drowned, Drained, Swamped & Bogged Down:

Initiating A Creative Exploration Of Mythterious Scottish Marshes & Wetlands

Landscape 1: Seven Lochs Wetland Park, Glasgow

Scotland's largest urban heritage and nature park. Between Glasgow east end and Coatbridge.

Habitats identified: Wet grassland, swamp, peat bog, reedbed, wet woodland, fen, springs/flushes/seepages.

Read about my landscape visit below and view my creative responses here.

This urban nature park spans seven lochs of varying sizes, habitats and atmospheres. They were created after the last ice age, as the ice sheet retreated and the huge blocks of frozen water left behind melted. Close to where I live in Dennistoun, my nearest loch, Hogganfield, is only a 10 minute bus ride away. I decided to take the train to the other end of the park and walk the 12 miles or so back home.

From Bellgrove station, the tower blocks, powerlines and graffitied backwalls of urban neighbourhoods turned first to a sea of static caravans and eventually to woodland. The park forms a corridor out to greener lands beyond the city’s sprawl - a lung for this underappreciated and historically-deprived area.

It was a chilly March day. Having lived in the southeast for 18 years, I had (foolishly) been expecting the landscape to feel alive with the buzz of spring by now. Instead, I was reminded of my childhood days in the Peak District, where things know to sleep still and dormant until real spring - the only movement until then is in the biting wind.

As the train moved off from Blairhill, it seemed like colour had been drained from the land with the exception of green moss which clung to most surfaces, soaking up the wet air.

But as I walked, the white-grey cloud parted to bright blue sky. Large black corvids took to swirling in the air above the dog walkers and joggers of Drumpellier Country Park, the “gateway to Seven Lochs Wetland Park”.

As I made my way towards Lochend Loch, the gloom of the silent flooded woodland beside the path was punctuated only by the colour of wind-blown waste - plastic bags snared among the drowned birch and willow. Flashes of green on the water caught my attention - not the male mallard that my mind’s eye saw, but a glass bottles, blinking in pools of light between the short wet trees.

Bursting hawthorn buds seemed out of place - winter was still very much present. Over the bridge and electric rails, I was through the gate into a different world…

Elephantine tree trunks rose to meet the path. The track was burnt peaty red and russet leaves had collected in sheltered spots beneath twisting spidery branches. The gulping of jackdaws yielded to the bright chirps of chaffinches and great tits - a sign that spring was now here. After a long dark winter I took a moment to breathe in the hopeful songs of the small birds - the life high above me sounded busy - but it was unseen.

I had already decided my first pitstop on arrival would be the Visitor Centre, which I knew from my pre-reading was close to the site of a Crannog - a type of ancient loch dwelling, which can be found throughout Scotland and Ireland. I knew there would be an artist’s impression of the Crannog inside the Centre, as well as essential supplies of tea and sandwiches ahead of the walk to come. Canada geese greeted me by the entrance.

It is mind-blowing that Crannogs were used as dwellings over at least five millennia, from the neolithic period onwards. From from primitive, our ancestors skillfully created these part- or wholly artificial islands from long timber posted embedded in the base of the loch to form a circle. Upon these stilts a walled wooden dwelling would sit above the water, accessed my a bridge, coracle or dugout canoe. The impressive structures are thought to have been built above the water as symbols of status rather than for security. The inhabitants - humans and livestock alike - would usually be covered by a cone-shaped thatched roof, allowing smoke from fires within to rise high above heads. The finds from Lochend crannog included the wood piles and cross timbers, quern stones for milling, hazelnut shells and bones both animal and human. The roof here was thatched with heather and wattle was daubed with clay from the loch banks to form walls.

The one found here would have been home to Iron Age people, who followed in the footsteps of the earlier Mesolithic hunter-gathers that camped and hunted on the shores of these lochs - following the animals and wildfowl with the seasons. The loch itself was once essential to sustaining human life here - its service to us returned through lazily discarded cigarette buts and floating crisp packets, echoing the orange bills of mute swans who floated alongside on the dark water.

After reading about the peat and spagnum moss that make the park so special, I departed the Visitor Centre and crossed the busy Townhead Road to reach Woodend Loch view point.

The arrival party there was a bullfinch - a rare burst of colour against the greyness of the loch, which is backed by powerlines. But I know from research how special this place is - now a Site of Special Scientific Interest due to the number of unspoilt wetland habitats found along the water’s edge, home to rare plants and beetles. I felt thankful that access is limited and therefore the loch is less-visited, allowing some peace for visiting summer ospreys. Paleolithic, neolithic and mesolithic items found near the loch indicate human presence in the area for ten thousand years or more. Stone tools found here in the 1900s and exhibited to Glasgow archaeological society in 1934, included flint blades made from flint, churt and mudstone, which were brought from other places or traded. Antler tipped harpoons were probably using to catch fish, while knapped stone arrow heads were likely used to hunt water birds. People of this period carried dried fungus to make fires, lit by striking flint on Iron pyrite (fools gold). Iron Age, while crafts included fired clay pots, jewellery- and bread making.

Boggy pools glowed burnt orange from organic matter or minerals leaching into the water.

After the flash of the bullfinch, the only other sign of life here today was more mute swans, whose beaks glowed against the grey.

I pressed on to Bishop Loch, the site of a second Crannog within the park, wishing either or both were visible above the water today. Then I thought about the lochs being pumped out by the steam machinery of eager excavators - the very thing that attracted those early people, drained away.

I encountered further signs about peat and moss, and yet more orange - this time glowing from the stems of twisted trees which rise out of the flooded bogs, like great tentacles. Stunted silver birch trees lined the edge of grassland and I began to appreciate quite what a rich mosaic habitat this is.

I pass what I assume is the result of fly-tipping (an ever-present threat to the wilder areas of Glasgow) and graffitied signs within Commonhead Moss Local Nature Reserve. People are trying hard to create spaces for both nature and nature-enthusiasts, but there is a sense they are struggling uphill against the enormity of the city’s polluting might - they need more resources.

Still, there is no doubting how special this place is. I have never seen a landscape like it. Thick spagnum moss forms large hummocks, seemingly out of proportion with the short birch trees which appear struggling to take hold in the shallow acidic peat, their height stunted. But this is how it’s meant to be. This is the uniqueness of this place and its wild inhabitants. Bar the electricity pylons looming above, which dwarf the trees further still.

I made my way through the maze of red twiggy birch to the viewing point and found a green bottle smashed on a stone “altar” - within its glass fragments the memory of some sort of modern day ritual.

The invisible border between the territories of Woodend Loch and Bishop Loch appeared ceremonially marked by an abandoned shopping trolley strewn on its side, its orange-red plastic parts radiating the cold light.

Wet clouds hung high above Bishop Loch, the deep blue backdrop made all the more vivid against the pale yellow-white stems of reeds and rushes - for now they were dreaming, but their old seed heads, which danced on the breeze, hinted at excitement for green renewal and warblers’ return.

Bare trees were reflected in water.

Two buzzards circled above the loch as tiny dots - the only movement in a still sky. I’d thought I might divert to Johnston Loch at this point, but the buzzards called me to follow the path onwards and I vowed to return to Johnston another time.

At busy Gartloch Road, distracted by the sight of roe deer along the woodland edge, I missed the footpath entrance for Frankfield Loch and erroneously head towards Garthamlock. I was rewarded with the sight of more deer, but realising my mistake I re-traced my steps and joined the path above Frankfield.

The sight of powerlines rising over bullrushes, the noise of dirt-bikers and an old rusty oil drum lying in shallow water reminded me I was on the city’s edge.

A tiny clump of moss on a branch - nature clinging on.

Crossing into Hogganfield Park I was greeted by the final loch on my walk and the sound of Canada geese, coots and black-headed gulls, who were making the most of ‘the best site in Glasgow for wetland birds”. I’d passed only one other person on the entire walk so far, but the buzz of people and familiarity was here - parents walking with children, wellies and dogs. The loch is now largely surrounded by development, giving it the feel of a desert oasis. Lush swords of green flag iris sliced up through the ground at the water’s margins. The day had brightened and the sky now bounced off the surface of the loch.

Legs too tired from the suck of boggy ground (or perhaps the laziness of city life returning?), I opted to take the take the bus the final stretch back home.

Leaving the sanctuary of the park I emerged from my mossy swan-infused dreams of watery crannogs and hunter-gatherers among the birch trees. Along almost the entire walk, the human detritus had threatened to wake me, but the spell was now well-and-truly shattered. I was wide awake with the roar of city traffic.

Close to the bus stop, I passed the rusty lifeless body of a deer, lying dead next to busy Cumbernauld Road - a stark and grisly reminder of why the park is so much needed.